Russia’s Occupation of Crimea: Blueprint for Eastern Ukraine?

Russian soldiers on the march in Crimea. Stop signs only work if there is fear of a fine. Photo: Reuters/Baz Ratner

After the Sochi Winter Olympics, Vladimir Putin has won a gold in the Occupation Olympics. They are being held in Crimea, just across the Black Sea from Sochi.

Putin managed to seize Crimea without firing a shot. Not bad for taking over a population 2 million people living on a peninsula slightly larger than Israel.

Will the Kremlin’s stealth blitzkrieg on Crimea now serve as a model for Putin to grab juicy chunks of Russian-speaking Eastern Ukraine, like the cities of Donetsk and Kharkiv?

Or has Monday’s dramatic 11 percent fall in Moscow’s stock market clipped the claws of the Russian bear?

Russia’s velvet glove invasion of Crimea displayed the same kind of ‘New Russia’ organizational expertise that we saw at the Sochi Olympics.

Here is the blow by blow:

First, armed men burst into Crimea’s parliament and forced legislators to vote for a new prime minister behind closed doors. Voting with guns in the room, this rump parliament elected a politician whose Russia Unity party had won three seats out 100 in Crimea’s last regional election.

With that democratic fig leaf in place, an incident was fabricated – a nighttime attack on the police headquarters in Crimea’s capital. The only problem: no neighbors heard shots, and no damage was shown to reporters.

Ukrainian soldiers wait inside the gates of their base Perevolnoye, Crimea, which was surrounded Sunday by 400 Russian soldiers and four Russian armored personnel carriers. Photo:AP/Darko Vojinovic

In response to that phony incident, Putin’s soldiers fanned out across Crimea, ostensibly to protect Russian-speakers — although none had been hurt. In an expertly choreographed operation, Russian soldiers surrounded all Ukrainian military bases, blockaded all ports and airports, and set up checkpoints with Russian flags on the two highways linking Crimea with the continent.

Although 13,000 Russian troops are believed to now be in Crimea, they all work in uniforms stripped in advance of insignia. Also indicative of the high level of planning, there were no reports of the foreign troops getting lost and asking for directions.

In the east, across a five kilometer strait from the Crimean city of Kerch, a column of Russian armored vehicles is reportedly massed at a Russian ferry landing. On Monday, Prime Minister Medvedev ordered a state construction company to start work on a $3 billion bridge across Kerch Strait, still an international waterway.

Oddly, as recently as Friday, Dmitri Trenin, director of Carnegie Moscow Center, was telling Western reporters that Putin was merely reacting to events, struggling to keep up. In reality, the invasion of Crimea followed a meticulously planned political-military blueprint. Crimea 2014 borrows a bit from Hungary 1956, a bit from Czechoslovakia 1968, and a bit from Afghanistan 1979

The occupation of Crimea is not the work of a rogue, hysterical admiral at the Russian Navy base in Sevastopol. Instead, a disciplined, unbroken chain of command runs straight back to the Kremlin.

For years, Russia prepared the political ground, bankrolling pro-Russian parties and associations in Crimea. Just last month, Vladislav Surkov, a top Kremlin political strategist, visited the peninsula. The new mayor of Sevastopol is a Russian citizen. Within hours of the arrival of Russian troops, crisp new Russian flags mysteriously erupted across Crimea, a strange sight in a region controlled by Ukraine since 1954.

Indeed after 70 years of control by Ukraine, it is unclear how many of Crimea’s Russian speakers really switched national allegiances overnight.

Germany’s 1938 annexation of German-speaking Austria, the Anschluss, was also greeted with smiles and the dismantling of border posts. Photo: Scherl

I have been to Crimea several times over the last seven years, visiting Yalta, Simferopol, Balaklava, and the Russian navy base city of Sevastopol. In Sevastopol, I talked to many people who were hostile toward Kyiv and the forced adoption of the Ukrainian language in schools. But it is unclear if Sevastopol residents speak for the 85 percent of Crimeans whose lives are not connected to this navy base city. Only 4 percent of Crimea’s population are believed to hold Russian passports.

My bet is that invasion opponents are lying low, waiting to express their views in the debate prior to a March 30 referendum on the peninsula’s future status. The choice: independence, continued autonomy within Ukraine, or absorption into Russia.

There is nothing terribly revolutionary about such a vote. The US territory of Puerto Rico, a former Spanish colony in the Caribbean, has held three such plebiscites since 1993. Scotland and Catalonia have similar votes planned.

But the Crimea vote will probably take place with the peninsula occupied by troops from Russia, a country where blatant ballot rigging in 2011 elections sparked massive public protest.

To have any credibility, Crimea’s poll will have to be overseen by international observers with serious democratic credentials. If the vote is rubber stamped by observers from Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia, the outside world will just laugh it off.

For now on Crimea, Ukrainian soldiers and Russian-speaking Ukrainian civilians are restraining themselves. Presumably, they want to avoid a shooting war between two Slavic Orthodox Christian peoples. But Kyiv’s government repeated this week that Crimea belongs to Ukraine. Ukrainian flags fly over many government buildings in Crimea. If a political solution is not found, anti-Russian guerrilla actions may follow.

The wild card in Crimea are the Tatars. This Muslim, Turkic speaking group accounts for 15 percent of the peninsula’s population. Crimean Tatars have big grudges against Russia.

Catherine the Great annexed Crimea in 1783, ending an independent Crimean Khanate. During 135 years under the Czars, relations between Tatars and Russians were often poor. But under the Soviets, they were disastrous. Civil war, famine and deportation cut the Crimean Tatar population in half.

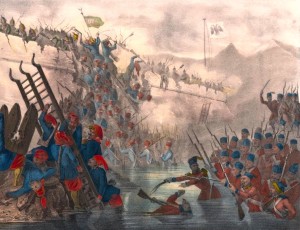

The Crimean War of 1853-56 became a big power confrontation resulting in 500,000 dead soldiers from Russia, Turkey, France, Britain and Italy. Here, Turkish soldiers storm a Russian fort.

In 1944, Stalin deported all Crimean Tatars to Central Asia.

That same year, he deported all of Russia’s Chechens to Central Asia.

We know the legacy of Chechen bitterness: two wars since 1991 against Russian rule.

How Putin would respond to violent anti-Russian resistance by Crimean Tatars? With the scorched earth anti-Chechen policies of the first Putin presidency? Or the waterfall of rubles for Chechnya of the second Putin presidency?

Mustafa Dzhemilev, a former Soviet gulag prisoner and leader of the Crimean Tatars, reacted to Russia’s March 1 invasion by writing: Crimean Tatars “will fight. Even if we have to physically fight the usurpers. Units of Crimean Tatars who are battle-ready are being formed now.”

And here, geopolitics come into play. Putin said Tuesday that his goal is not to annex Crimea. But if he sets up a puppet republic, like Georgia’s Abkhazia, he will be stripping Ukraine of much its coastline and boldly asserting that the Black Sea is a Russian lake.

But, how would Turkey see the expansion of Russia’s coastline and territorial waters by 1,000 kilometers? Probably not well. Especially, if it comes with curbs on Crimea’s Tatars, Turkey ethnic and linguistic cousins. The Crimean Tatar diaspora has an influential lobby in Ankara.

For two centuries – from 1676 to 1878 – Russia fought 12 wars with Turkey over Black Sea real estate. The Crimean War of 1853-1856 drew France and Britain to the side of the Turks. Today, European powers are not threatening military action over Crimea. But from the point of view of Turkey, a NATO member, Kremlin control of Crimea would shift a balance of power that has existed in the Black Sea for a generation.

If Russia does not handle Crimea’s Tatars and Turkey with real diplomacy, Turkey can retaliate by blocking Russia’s oil shipments through the Bosphorus. About one third of Russia’s oil exports pass through that strategic choke point.

So what started as a smooth occupation of Crimea, could get quite messy, quite fast.

And how did the last Crimean War end in 1856?

Russia lost to an alliance of Turkey and the West. VOA

Russia lost to an alliance of Turkey and the West. VOA

No comments:

Post a Comment