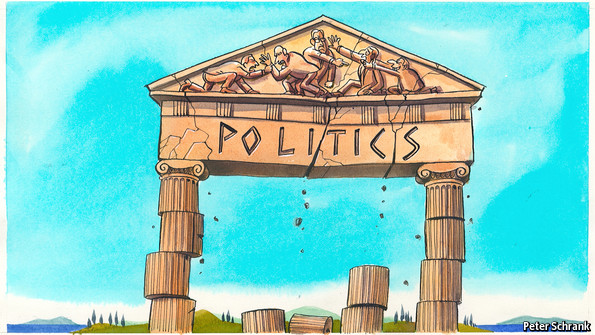

Remaking the political landscape

A new burst of optimism about the economy is not yet luring many voters back to the two mainstream parties

GREECE’S chances of recovery after six years of misery are improving. Its first bond offering in four years, seen as a test of confidence, did much better than expected. Tourists are flocking in for Easter; hoteliers predict a record 19m visitors will come this year. One long-blocked resort project on Crete seems poised to go ahead, raising hopes that foreign investment may flow into other industries such as electricity and ports. Angela Merkel, the German chancellor and often one of Greece’s harshest critics, spoke encouragingly to young Greek entrepreneurs during a quick visit to Athens on April 11th.

Yet the new optimism does not seem to be trickling down to most voters. Unemployment fell slightly in January, but still stood at 26.7%. The social safety-net is stretched so thin that only one in ten of the unemployed gets any benefits. Private-sector workers complain of being paid months in arrears. An estimated 35% of Greeks now live in poverty, according to social workers and charities.

Advertisement

No wonder Greece’s clientelist political system is in tatters. It was once a politician’s responsibility to find jobs in the public sector for his (rarely her) constituents. Ambitious MPs extended their patronage to the private sector. “My application for an assistant supermarket manager’s job was picked on merit, but it wasn’t approved by the local MP—he wanted someone else,” says Simos, a 28-year-old economics graduate now working in Germany.

Angry voters used to shout “Thieves, traitors” outside parliament as lawmakers waved through a string of unpopular reforms demanded by Greece’s creditors. The centre-right New Democracy (ND) and the PanHellenic Socialist Movement (Pasok), partners in a fractious coalition with only a two-seat majority in parliament, are now widely blamed for the collapse of the patronage system that they built during 30 years of alternating in power.

Some voters have switched instead to “anti-systemic” fringe parties that advocate extreme solutions to Greece’s woes. At next month’s European elections, being held at the same time as local elections, two new moderate centre-left parties, Elia (Olive tree), led by a group of academics and former ministers, and To Potami (the River), led by Stavros Theodorakis, a television journalist, are trying to plug the gap opened up by Pasok’s slump.

Many on the left now back Syriza, a radical left-wing party led by Alexis Tsipras, a fiery 39-year-old who scares Greece’s businessmen with talk of imposing a wealth tax and suspending debt repayments. Evangelos Venizelos, the Pasok leader (and foreign minister), is fighting attempts by George Papandreou, a former prime minister, to reassert authority over the party founded by his father Andreas, Greece’s first Socialist prime minister. Mr Venizelos backs Elia, but Mr Papandreou refuses to join him, prompting speculation that he seeks a political comeback to stop his dynastic party disappearing.

ND has proved Greece’s most durable party, surviving several changes of leadership. Yet its voters provide much of the support for the neo-Nazi Golden Dawn, a homophobic, anti-immigrant party whose 18 deputies are accused of running a criminal organisation. Embarrassingly for Antonis Samaras, the prime minister and ND leader, a leaked video showed his chief of staff, Takis Baltakos, telling Ilias Kasidiaris, Golden Dawn’s spokesman, that the public prosecutor had found barely a shred of evidence against him. Mr Baltakos quit; and the affair has had little impact on ND’s poll rating. Mr Samaras is far ahead of Mr Tsipras as “most suitable prime minister”.

Opinion polls nevertheless give a slight edge to Syriza over ND, with both parties consistently on 18-20%. Pasok has sunk to around 3.5%, and could fail to win any European seats. More than three-quarters of Greek voters would like Mr Papandreou to retire from politics. Golden Dawn has fallen from 11% to about 8%, but it could bounce back on a sympathy vote if Mr Kasidiaris, who is running as Golden Dawn’s candidate for mayor of Athens, is placed in custody before polling day on May 25th.

Elia is polling around 5% but is seen by many as a dull and outdated revamp of Pasok. But To Potami has picked up voters at dizzying speed, moving into third place, with 11-15%, within three weeks of its launch. The 50-year-old Mr Theodorakis, wearing a T-shirt and trainers and carrying his trademark backpack, tours the country making low-key speeches about cracking down on tax evasion, promoting meritocracy and creating jobs for young Greeks. These are soothing sounds for voters fed up with traditional politicians.

Some analysts claim that To Potami is backed by powerful business interests determined to stop Syriza and, perhaps, to force Mr Samaras to call an early general election later this year. Mr Theodorakis insists his party is financed by small donations. Questioned by a Pasok deputy about his party’s finances, he snapped back, “It takes a lot of chutzpah to ask about our campaign when your party has dumped €140m on the Greek taxpayer.” He was referring to unpaid bank loans run up by Pasok when Mr Papandreou was in power. Greece’s political landscape is shifting—perhaps for the better.

No comments:

Post a Comment