Over a century after the abolition of slavery, Brazil has become a hub of international human trafficking. Illegal migrants are coming not only from neighboring Latin American countries but from as far away as Asia.

Brazil's booming economy is not only attracting migrants from impoverished neighboring Latin American countries, but more recently emigrants from Asia. In the past week, a human trafficking ring was uncovered near the capital, Brasilia, for the first time.

The liberation of 80 Bengali laborers in Samambaia, a suburb of Brasilia, shines a light on the dark side of Brazil's rise to economic and political dominance within the region. "We are concerned," says Arnaldo Jordy Figueiredo, chairman of the Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry (CPI) on human trafficking. "It's the first time forced laborers from Bangladesh have been discovered here."

The inclusion of the largest Latin American country in the lucrative global human trafficking trade took place gradually and went largely unnoticed. In 1995, the Brazilian government began systematically combating human trafficking and slave labor. Since then, official figures suggest some 44,000 people have been released from slave-like conditions.

The business of poverty

With the World Cup and Summer Olympic Games to be held in Brazil in coming years, forced labor has become more international and shifted from the country's interior to the cities. Illegal exploitation of workers now mostly takes part on construction sites, in cold storage facilities and within the textile industry.

"We have to find a scheme that prevents human trafficking and controls labor migration," Rodrigo Souza do Amaral, a Brazilian foreign ministry diplomat, told the Agencia Brasil news agency.

The business of poverty is flourishing, the 80 Bengalese who were discovered by federal police in Samambaia paid up to $10,000 (7,684 euros) to come to Brazil. They had apparently been told they would earn $1,000 to $1,500.

The business of poverty is flourishing, the 80 Bengalese who were discovered by federal police in Samambaia paid up to $10,000 (7,684 euros) to come to Brazil. They had apparently been told they would earn $1,000 to $1,500.

Gateway to the Amazon

Most immigrants are smuggled across the north of the country through Bolivia and Peru, or Guyana and into Brazil. In the border town of Assis Brasil, the military had to be deployed to help the town's 7,000 inhabitants, who were overwhelmed by the onslaught of Haitian refugees. The list of countries from where migrants are emigrating is long: including Bangladesh, Bolivia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Nigeria, Pakistan, Senegal and Sri Lanka.

Most of the migrants do not stay in the Amazon, but move on to major metropolitan centers. Estimates by the NGO Reporters Brasil suggest that more than 300,000 illegal immigrants from Bolivia and Paraguay live in the greater Sao Paulo area, as well as 70,000 from Paraguay and 45,000 from Peru, most of whom work in slave-like conditions.

"Manpower is not lacking," CPI's Jordy Figueirdeo told DW, adding that the exploitation of illegal immigrants pushes down wage levels and sets in stone precarious working conditions.

"Manpower is not lacking," CPI's Jordy Figueirdeo told DW, adding that the exploitation of illegal immigrants pushes down wage levels and sets in stone precarious working conditions.

The focus of investigations by Brazil's labor ministry is clandestine textile production. In Sao Paulo, a total of 50 sewing workshops, in which migrants were working up to 16 hours a day for starvation wages, have been shut down. Among the customers, according to the ministry, are internationally known companies such as Zara, Gap and Gregory, as well as the Brazilian chains Lojas Marisa and Pernambucanas.

Harsher penalties for companies

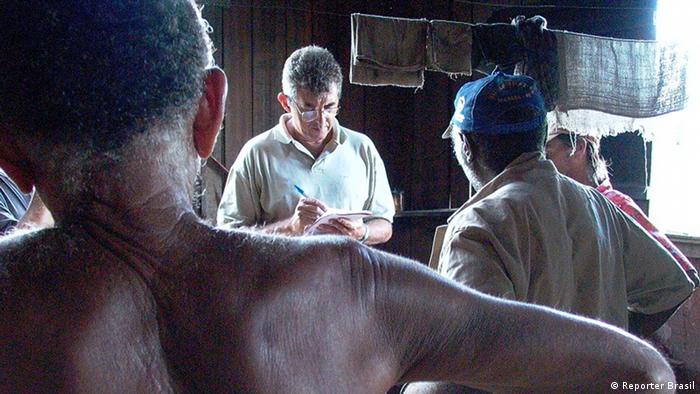

"The ministry inspections in past years has prompted a debate about slave labor and human trafficking like never before," explained Renato Bignami, regional supervisor for the ministry in the state of Sao Paulo. In inspections on location, parliamentarians had been able to see contemporary forms of slave-like labor for themselves.

Meanwhile, four different parliamentary inquiry committees at federal, state and local levels have begun concentrating on the problem. The parliamentary commission's mandate was extended by Brasilia for the fourth time in late May.

As a direct result of public debate, the legislation was changed. Firms operating in Sao Paulo state will lose their operating licenses for 10 years if slave-like working conditions are discovered by authorities. In future the authorities will be able to repossess property on which slave labor occurs throughout Brazil.

Under Portuguese colonial rule, African slaves were the mainstay of the Brazilian economy. Ironically, 125 years after the abolition of slavery inhumane working conditions have returned through the back door.

No comments:

Post a Comment